Git 2 - Under the Hood

A more in-depth examination of how Git works

Introduction

A few weeks ago I posted a long article about Git basics, and on some concepts I promised a second, more in-depth article looking into the internal workings of Git. Well, here it is! Today we’ll be going over how Git works in a deeper way.

Git Layers

One way to make Git’s inner workings easier to understand is to imagine it as having layers (kinda like an onion…?). Looking at it from the outside, as a complete distributed version control system, is a lot to take in at once. Here we’ll be organizing our discussion about Git as looking at each layer individually, from the inside out, to make it a little easier to wrap our heads around.

If we want to peel back these layers, we can imagine it going a little bit like this:

- We start with the entirety of Git, and we understand it to be a distributed version control system.

- The first layer we might find easy to peel away is that pesky ‘distributed’ part. Without that, we’re left with a version control system, which on its own is still complicated.

- Next, we could try and remove the more complex aspects of that, such as branching and complete project history. Without those, we have a system that just tracks content; a stupid content tracker (which is what Git calls itself in its own manual!).

- To get to the innermost, most basic level, we can even remove the concept of tracking files, versions, and the concept of a commit itself. When we strip all that away, we’re left with a persistent map.

Level 1: Persistent Map

A map is a simple structure that maps keys to values. In Git’s case, it’s also persistent, which just means that it’s stored in a long-lasting medium, like on your computer’s hard drive. So, on this level, Git is a system that maps keys to values, and this information is stored on your computer so it can be accessed long-term.

A map of values and hashes

So how does Git’s map work? It uses values and hashes. A value, at its most basic, is just a sequence of bytes. Any sequence of bytes can be a value. It could be the content of a text file, a binary file, anything, as long as it reduces down to a sequence of bytes. Anytime you hand Git a value, it’ll calculate a key for that value, using hashes.

Git calculates hashes using the SHA1 algorithm (short for Secure Hash Algorithm 1). SHA1 hashes are exactly 20 bytes in hexadecimal format, so a sequence of 40 hex digits. A SHA1 hash is always the same for exactly the same content. For example, the SHA1 hash for string “Hello World” is “0a4d55a8d778e5022fab701977c5d840bbc486d0”. It’s the same whether I put that string through the algorithm, or you do. Try it!

These generated hashes are Git’s key to storing content in the map. If you have the key, you can access the value associated with it. Every object in a Git repository has a hash associated with it (and more about objects in a second). In practical terms, the hashes generated while working on a project are going to be unique not only to your project, but also the universe. It’s technically possible to get a duplicate, but given how large the number of possible permutations are in a hash that size, it’s incredibly, incredibly unlikely (like, numbers too large for your brain to really quantify levels of unlikely).

Storing things

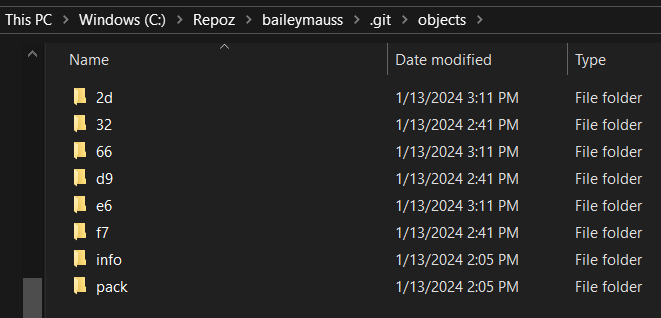

Now we understand how Git is a map, but it’s also a persistent map. What we mean by that here is Git is storing things on your PC’s disk. In your .git directory (which is usually hidden by default), there is an ‘objects’ folder that Git uses to store, you guessed it, objects. The scheme Git uses to do so, though, is interesting. For every object Git stores, it first takes the hash of the object, then creates a subfolder that starts with the first 2 digits of the hash. Then, inside that subfolder, it’ll create a file, named the remainder of the hash (everything except the first 2 digits).

When Git does this, it adds a header and compression, so we couldn’t just open this file and read from it directly. If you were curious, though, you could use the command git cat-file -p to get the content from the file. Git calls this object a blob, which is just a chunk of binary data.

Objects

When it comes to objects, as far as Git is concerned, there are only 4 types: blobs, trees, commits, and annotated tags. At this complexity level, we really only need to worry about blobs and trees.

Blobs can be understood kind of like a file, as it stores contents of a file, but blobs have no specific attributes of any kind: no file name or type, so they’re really generic.

Trees are a simple object that contain a bunch of pointers. Those pointers can point to other trees, or blobs. A tree is like a directory. If a tree contains a pointer to a blob, that tree contains file content, and if it points to another tree, that’s a subdirectory of the tree. A tree can have as many of these at once as it needs to; it’s like your file system on your computer.

If this is still a bit confusing, and you’re wanting some more reading on the Git object model, here would be a good place to start.

Level 2: Stupid Content Tracker

To justify calling Git a stupid content tracker, we really only have to add one more thing: versioning.

Commits

Let’s look at the commit object type for a moment. A commit contains a reference to a tree. By containing a reference to a tree object, it represents the state of the file directory at the point in time the commit was made. Commits also contain a reference to another commit. Why? Because commits are linked: most commits have a parent (the very first commit you make would be an exception). If you’re familiar with data structures, they work similarly to a linked list.

A good amount of what Git does to manage versioning is having a lot of pointers. For example, say you have a commit where just one file in your project was edited. The tree will point to a newly created object for that edited file, but the pointers for all of your other file objects will stay the same; Git creates exactly one hash for one object. Git is really concerned with efficiency, so it’s not going to store the same thing more than once.

Level 3: Version Control System

What differentiates a version control system from a stupid content tracker, in Git’s case, is branching, merging, rebasing, and tags.

Branches

Branches are what start to make Git a bit more sophisticated, if a little more complicated. But under the hood, branches are surprisingly simple. A branch is just a reference to a commit. That’s it. Don’t believe me? In its .git directory, Git stores branches in the references, literally /refs/, folder (specifically, /refs/head/).

Git does have to keep track of a little more information to maintain its branching features, though. Git keeps track of which branch is the current branch in the HEAD file. The HEAD file is just a reference to the branch file. Remembering a branch is just a reference to a commit, HEAD is just a pointer to a pointer. Anybody else remembering their C programming days right now?

When we switch branches, Git does two things. The HEAD pointer changes to point at the branch we’re switching to, and Git replaces the files and folders in our working directory with the files and folders in the commit our new branch is pointing to.

Off with your HEAD

If you wanted to, it is possible to switch directly to a commit instead of a branch. When you do this, HEAD isn’t pointing to a branch anymore, but directly to a commit. Now, Git is in a state of having no current branch. Getting yourself into this scenario is called having a detached head. In this situation, when you make changes, stage them, and commit them, Git can’t move the current branch (because there isn’t one!). The only option Git has is to track this newest commit with HEAD directly. HEAD is now acting like a branch here. Cool, so what’s the problem?

What if you switch back to a branch? We know when we do this, HEAD now points to that branch. The commits we made under our detached HEAD still exist in the object database, but unless we took note of their hashes, those commits and their connected objects become unreachable, since we had no branch pointing to them. And knowing how much Git cares about efficiency, you might be able to guess what Git does with unreachable objects: it eventually garbage collects them.

Now, if you wanted to recover those objects, as long as you have their hash, you could navigate back to it and put a branch on it for safekeeping. In general, you can use a detached HEAD to experiment since it’s safe to discard afterwards, but with any content you care about, put a branch on it!

History and Content

Like we discussed earlier, the only types of objects that exist in Git’s database are commits, trees, blobs, and annotated tags. In a project, all of these types of objects are arranged in a graph, and they all reference each other. There are references from a commit to its parents, references from a commit to its tree, references from trees to blobs, references from trees to other trees… etc. These references all look the same, but there’s two different ways they are used:

References between commits are used to track history

All other references are used to track content

When you move from one commit to another, like when you switch branches, Git doesn’t care about history: it doesn’t look at the way commits are connected to each other. It looks at the tree in the commit and all of the objects that can be reached from there. Git then uses this information to replace the contents of your working directory, and now you’ve changed branches. This is how Git time travels!

Git’s system for managing content is also simpler than it appears. Retrieving a past state of your project is pretty straightforward: all Git does is go into a commit and retrieve trees and blobs from there. As the end user, it can seem a lot more complicated and difficult to understand, but using Git becomes a lot easier if you focus on the history and understanding how your commits are linked to one another, and trust Git to do the right thing in handling trees and blobs.

It’s also worth knowing that Git, for the most part, does not care about your working directory. When you move between commits, Git just replaces the working directory with stuff from the object database. What Git does care about is the objects that exist in the database. Database objects are immutable and persistent, and Git protects them as such, but files in the working directory are regarded as transient. However, even though Git doesn’t really care about the working directory, it isn’t reckless with it either. It’ll warn you if you’ve asked it to do something that will overwrite your files.

Merges

Merges, as seems to be the theme today, are pretty simple. A merge is, by definition, a commit with two parents instead of one. I don’t know about you, but that blew my mind just a little bit learning that (but it’s possible I am easily impressed). It makes perfect sense, though: you’re taking two branches, which we know are just references to commits, and combining them.

If you’ve ever been notified when merging that Git performed a fast-forward merge, that’s essentially Git flexing its frugal muscles for you. A fast-forward is like a merge without merging; all Git has to do is move the branch pointer up to a newer commit, no new commit object necessary. This saves space and resources, so Git always prefers to do this when possible.

Rebasing

As not many version control systems have rebasing, you could see it as Git’s signature feature. We know that rebasing is another way of bringing two branches together, like merging, but works a bit differently. Taking the two branches we want to combine, Git finds the “common ancestor” commit, which is the most recent commit both branches have in their history. Then, one branch’s history after that point is detached from that common ancestor commit, and is moved to the top of the other branch’s history. It changes the base of that branch, aka ‘rebasing’. That’s a solid way to explain rebasing to a human, but what does Git actually do when rebasing?

How rebasing really works

When rebasing two branches, Git makes copies of the commits then creates new commits with exactly the same data except for their parents (and except any merge conflicts you might have to fix during the rebase). Aside from those changes, the new commits look almost exactly like the originals. However, they are new objects, with new associated hashes, and they are new files with new names in the database directory. Git moves the rebased branch pointer to point at the new commits, leaving the old commits behind. At this point nothing is pointing to the old commits, so they’ll eventually be garbage collected. Rebasing can be a bit tricky to wield, but it’s helpful to remember it’s an operation that creates new commits in place of old ones.

Rebasing vs. Merging

So, why even have both rebasing and merging when they kind of accomplish the same thing? As with many things, it’s because there’s trade-offs to using both.

Trade-offs to merging

The whole point of merging is that it preserves project history exactly as it happened. In general, preserving history is a good thing, with the exception that sometimes the history is complicated and confusing, so it isn’t necessarily a good thing. Additionally, any fixes to merge conflicts that occur are included in the merge commit. Merging is just simpler, but it becomes not so simple when you’re looking at a large project with a lot of merges. If you’ve ever checked the git log, its history can be deceiving when working on this kind of project, since git log is displaying project history to you as a single line, when it would be more accurate to represent it as a graph.

Trade-offs to rebasing

The primary advantage of rebasing is that a rebased project history looks really simple and neat. A project that uses a lot of rebasing, as opposed to merging, looks a lot more streamlined and clean in its history. Rebasing can be thought of as a way to refactor your project history so that it looks nicer and is easier to understand at a glance.

Of course, this neatness comes at a cost. Unlike merges, a rebase alters the project history. This nice and neat project history isn’t real, but rather forged through rebasing, which is technically destructive since it’s creating new commits and leaving old commits behind. It’s worth considering there may be situations where you do care about accurate project history. For example, there are advanced Git commands that become less useful when working with an altered history, or it could cause issues with distribution. Rebasing is kind of like a power tool: it’s quite useful, but you should only be using it if you know what you’re doing and understand the potential consequences. When in doubt, just merge!

Tags

Tags function as a label for a commit. These are used to mark specific points in a project’s history as important, like release versions. There are two kinds of tags: a simple, lightweight tag that just contains a label, or an annotated tag that contains additional metadata. A tag is made up of two components: the tag metadata, and a pointer to a commit. Lightweight tags just have a name, and point to a commit. They don’t even need to be considered an object, since they don’t need a place to store additional metadata. Annotated tags are the last type of object we haven’t really talked about until now. An annotated tag is an object: it points to a commit, but it also has metadata such as the author of the tag, the date of tag creation, and a message within the tag.

Tags are very similar to branches. In particular, a lightweight tag is almost identical to a branch. The main difference is that tags don’t move as you work. A branch will move to keep track of new commits, but a tag will stay where you’ve placed it, sticking to the same object forever.

Level 4: Distributed Version Control

Now we can add back in the final layer of Git: what makes it distributed. With this, we add back in the existence of remote repositories and working with multiple contributors on a centralized project.

Remote repositories

When you use git clone to get a copy of a repository, you aren’t just getting the project files. You’re also getting a copy of the .git directory. Additionally, unless you specify otherwise, you aren’t getting the entire repository, but just the main branch. When working with both remote and local repositories, your local repository needs to remember the location of the remote, and it does this by storing it in the .config file. At the time of cloning, Git automatically defines a default remote source and uses the convention ‘origin’ as its name. The default configuration of a repository also defines that we must have a main branch on our local repository that maps over the main branch of the remote source.

In order to synchronize the remote and local repositories, Git has to know the current state of the origin repository. Git tracks remote branches much in the way it tracks local ones: by including the branches as references in the /refs/ folder. When you connect to the remote repository, Git automatically updates its information on the status of the remote.

Because Git objects use SHA1 hashes that are unique in the universe, it’s actually really easy to synchronize repositories without getting confused. Git can simply copy missing objects from one repository to the other. However, this is exactly why rebasing should never be done on shared commits: because rebasing creates a commit that looks identical but is different, in its name and as an object, doing this will create conflicts for everyone (and a messy history that is difficult to understand, which defeats the purpose of a rebase in the first place).

Distribution Features in GitHub

GitHub includes some additional features that aren’t inherent to Git, but add some utility when working in a distributed environment.

Forking

Forking is like cloning, but remote. It brings a project from someone else’s GitHub account to yours. As far as Git knows, there is no connection between your project and the original. GitHub knows there’s a connection, but Git does not. Because Git doesn’t know that, if we want to keep track of changes to the original project, we need to add another remote pointer. The conventional name for this connection is ‘remote upstream’. After doing that, your local project now has two remote connections: your origin and your upstream. This should help make the difference between the two types of connections more clear.

Now, because we have no permissions to the original project, we can’t directly push any changes we make to that project. To do that, we’ll need to use pull requests.

Pull Requests

Pull requests enable us to basically ‘suggest’ changes to that original project that doesn’t belong to you. It’s like sending a message to the original project’s maintenance team. If the owner of the project likes your changes, they can choose to approve the request and pull the changes into the original project. This is commonly how open-source projects are worked on and improved by many people without any professional connection!

Conclusion

On its face, Git can seem like a complicated beast, and in some ways it is, carrying a reputation of a steep learning curve and little hand-holding. I have found, though, that learning how it works on a deeper level and in smaller pieces makes it seem much more approachable. I hope you found something helpful in this post, and I look forward to returning soon with a post on a different topic.