Back to Basics with Git

A review of the fundamentals of Git

Introduction

To begin my process of refreshing my skills, it made the most sense to me to start with a full review of Git. Not only is it going to be useful for virtually any project I’ll do in the future, but it’s also a core skill for almost any developer and probably many non-programmers as well. I’ve worked with Git plenty in the past, but never took the time to formally educate myself on the complete picture of how Git works. I learned a lot of conceptual things that hadn’t been mentioned to me before and maybe you will too! This first review will be a fairly surface-level look at the concepts behind Git, and more conceptual than it is technical, but I’ll also be writing more in the future about the inner workings of Git so keep an eye out if that’s something that interests you.

Why Version Control?

Well, what is Git? The most straightforward answer is a free, open source, distributed version control system. So what do all those words actually mean?

Free

Free, in reference to software, refers to the ability the users are afforded (per the license) to run, use, copy, distribute, and modify the software as they see fit. This is often discussed in tandem with open source, and the two concepts have plenty of similarities, but aren’t exactly the same. I won’t get too bogged down with philosophy here. For now, you can find some more information on free software here.

Open Source

Open source is commonly understood as software whose source code is available to anyone to modify and is often built and improved by a community of people who do so out of the kindness of their hearts and a passion for the craft. And while this isn’t necessarily incorrect, it’s a bit narrower in scope than the open source initiative defines it. Similarly to free software, it refers to the licensing of the software that allows users to use, modify, study, and distribute the software and source code to their hearts’ content. Further reading on the criteria of open source can be found here.

The Distributed System

Being a distributed system is fundamental to Git. It’s a big part of what differentiated it from older version control systems that were popular before its arrival. Git was not the first distributed version control system, but it did popularize the distributed model. My dad, a developer of 20 plus years, tells scary campfire stories about what everyone did before Git, having to check out files like you were in a library, and the painful integration phase. So what’s so life-changing about your version control system being distributed?

Where the older centralized version control systems used a client-server approach, a distributed version control system uses a peer-to-peer approach. Every contributor to a project has full access to the codebase and its history on their machine, as well as their own copy to work on. There’s no need to maintain a connection to a central server. Each person that works on a project can be productive as long as they have their computer. They can make changes and mistakes to their hearts’ content, and it will be of no consequence to any other contributor until the changes are intentionally shared with the remote copy. In fact, the only time it’s really necessary at all to communicate with another source is when it’s time to share changes. A lot of the operations of the system are faster, and Git is very concerned with being as lightweight as possible.

Version Control

Finally, version control. It’s not hard to imagine what it might be good for. Version control just refers to the process of saving versions of a project throughout its life cycle, enabling you to retrieve past versions whenever you’d like. It allows for a lot of freedom to try out new ideas without fear that you’ll accidentally ruin all of your hard work. It keeps your work safe. Something of interest about Git, and distributed version control systems in general, is that its approach to this has less to do with versions and more to do with changes. Git keeps track of your files and when changes are made, it notes what and where and when. It knows what exactly changed between commit 1 and commit 2. The end result is the same, a complete history of your project at any given point in time, but it is a different way of going about it than version control systems used to.

That was a lot of words trying to define a few terms, so let’s get to know Git.

Git Characteristics

A few key things about Git that really help in understanding how it works, and how to work with it:

Git is explicit

As opposed to implicit programming, where some code is executing something for you behind the scenes, Git is explicit. It isn’t going to do anything without you clearly telling it what you want done. And while this can be frustrating when first working with it, it does afford you complete freedom to tell Git exactly how, where, and when to do things.

Git “snapshots”

Git saves changes to a project, or commits, as a complete “snapshot” of the project’s file system. You can, of course, ask Git for a file’s changes (a delta or a diff) and it can give you that information, but every commit is going to have a picture of what the entire project looked like at that time. That might sound weird, considering a couple paragraphs ago I said Git thinks about things in terms of changes rather than versions, but both are actually true. To explain how, we’d have to discuss a bit more about how Git works under the surface. I want to keep the scope of this article more surface-level, so we’ll discuss this in more in-depth in the future. The important thing to know is Git knows what your entire project looked like every time a change was made, but when working with Git it’s more helpful to not focus too much on versions. More about this here.

Git is optimized for local development

Git makes working on a project in your local environment very easy. You have a complete copy of the project and its history on your machine! You can be completely offline on vacation in the Maldives and still have access. The caveat here is if you’re working on a project with others in a shared repository, you only have the up-to-date changes from others as often as you’re retrieving them, but that’s okay. Git has strategies to make everyone’s changes work harmoniously. You can work away from the shared repository, then come back online to share your changes and get caught up on others’ work.

Git is designed for non-linear development

Git enables you to work on different versions of your project at the same time. It does this by utilizing branching. Branching is not a new feature to Git but it’s very helpful and relatively inexpensive on your resources (Git does everything it can to be as lightweight as possible… more on that later). You can have as many different versions of your project as you’d like, and you can work on whichever branch or switch between branches to your heart’s content. This allows for a lot of freedom in trying out a new feature or idea while being able to keep it separate from the rest of your work.

Git Concepts

File states and statuses

Files have a kind of life cycle within Git. Git assigns files a state and/or a status depending on what you’ve done with the file. To start with, a file can be in one of two states: tracked or untracked. Recall that Git is explicit in nature, so when a file is first added to a project, Git is not going to automatically begin tracking it. You have to tell it you want it to track that file. (We are talking about using Git in the command line here. Depending on what program you use to write your code and if you use a software to work with Git, you may not have to worry about this too much. Conceptually, though, it’s good to know.) Once Git is tracking a file, it won’t stop tracking the file until you tell it to do so. It’s worth noting that telling Git to stop tracking a file is a destructive command, as you’ll lose Git’s metadata and tracking on the file, so proceed with caution. It’s unlikely this is something you’ll do often, if ever.

Files that are in the tracked state can have one of three statuses: unmodified, modified, and staged.

Unmodified means that the file is being tracked, but the file hasn’t undergone any changes since the last time it was saved, or committed to the project. A file can’t be in this state until it has appeared in a commit, so new files won’t be here until they’ve been committed at least once.

Modified means that a file has undergone changes, but has not yet been committed or staged to be committed.

Staged means that a file has been changed and has been added to the ‘staging area’, or the pre-commit stage. When a commit is performed, any files that were staged are saved as part of that commit, and those files return to the unmodified status. The difference between a modified file and a staged file will make more sense when we go over Git’s directories, which we’ll do now.

Git’s 3 Directories

Git has 3 directories that help it keep files organized. These directories do a similar thing to file statuses: they reflect the life cycle of a file as it exists and changes within your project.

The first directory utilized by Git is your local history. When you first initialize Git to a project, it creates a hidden directory called .git/ at the root of your project. This directory contains all of the Git metadata and tracking, along with all your saved versions or commits of your project. Files in the ‘unmodified’ status live here!

Then we have our working directory. This can be thought of as your workspace. Files exist here when changes are being made to them, and files here will always be thought of by Git as being actively worked on. This is where files in the ‘modified’ status will be.

Finally we have the staging directory, also called your index or cache. When you’ve made some changes to a file and think it’s probably ready to be saved, you’ll add the file to the staging area. This isn’t the same as actually performing a commit, it’s more like a pre-commit step so that you can ensure everything is looking the way you want it to before finalizing it.

So, throughout the life cycle of a file in your project, it will exist as an unmodified file in your local directory, when you make changes it will become a modified file that lives in the working directory, and when you stage it to be committed it’ll become a staged file living in the staging directory. Once you perform that commit and the changes are saved to your project, it returns to the local directory and becomes unmodified again. It’ll go round and round for as long as you are making changes to it!

Git Configurations

Git configurations can be applied at three different levels. They can be done at the system level, which applies to all users on the same machine, the global level, which applies to all repositories created by the same user, and the local level, which applies to just one repository. If you don’t specify a level when setting a configuration, by default Git will apply it locally. Each level’s configurations will trump the configurations on the level before it, so a local configuration will be applied over a conflicting global configuration, a global over a system, etc.

Common Git Commands

Out of over 100 commands (and not even mentioning all the options for all of those commands), there’s about 20-30 common commands that’ll get you through most things the average person would need to do with Git. There are high-level commands (sometimes called porcelain commands) that are commonly used day-to-day, which are what we’ll be talking about here. There’s also low-level commands (sometimes called plumbing commands) that access the inner workings of Git. Most of those commands aren’t really intended for use in the command line, but used in scripting or tools, and we aren’t going to be concerned with those.

The first useful thing to know is Git has a ‘help’ subcommand that can be run with a command to get more information about it and what it does. That looks like git <command> –help1. Git also has a full manual available by running man git, but that manual is pretty long, so it might be easier to run git help, which gets you a shortlist version of the manual with the most common commands.

Basic commands

| command | description |

|---|---|

git init |

Creates a new .git repository |

git add |

Moves files into the staging area |

git status |

Displays information about the status of your git repository and files |

git commit |

Records changes to the repository |

git config |

Gets and sets options |

git log |

Displays commit logs |

git diff |

Displays file changes that exist in each file status |

git mv |

Moves or renames a file |

git stash |

Records current state of working directory and staging area then cleans working directory |

Branches

| command | description |

|---|---|

git branch |

Lists, creates, or deletes branches |

git checkout |

Switches branches, creates branches, many different uses; older command and more stable |

git switch |

Newer command solely for switching branches |

git merge |

Brings changes from one branch into another |

Repositories

| command | description |

|---|---|

git clone |

Copies an entire repository into a new local .git directory |

git remote |

Displays linked repositories, or manages connections between repositories |

git push |

Sends changes on your local repository to a remote repository |

git pull |

Retrieves and integrates changes from remote repository to your local repository |

git fetch |

Retrieves but does not integrate changes from remote repository |

Undoing changes

| command | description |

|---|---|

git revert |

Creates a new commit that undoes a previous commit |

git reset |

Resets file changes in the working directory and staging area |

git rm |

Stages file removal and untracks the file |

Local Repositories

Let’s look at using Git in a purely local, solo project kind of way. The first thing you’ll have to do is install Git, if you haven’t already. This page has instructions on how to install Git for Linux, MacOS, and Windows.

Adding Git to an existing project

If you already have some project files, and have decided you’d like to use Git, you can do that! In your command line (and all operations in this post will be referring to command line use), in the root directory of your project, running the command git init will make the directory a Git repository.

Adding new files

Now the project will have a .git/ directory, but it won’t yet be tracking any of your existing files. Running git status will also warn you about any untracked files in the project folder. To track these files, you can run either git add . (to add everything in the folder) or git add <file or folder name> (to add specific items). Git add takes those files and puts them in the staging area to be committed, and the files are now being tracked. The only thing left to do is run git commit so that those files now exist in Git’s record of your project’s history. Though really, best practice would be to run git commit -m “<Commit message here>”, so that your commit also contains some information on what was changed in this commit.

Making changes

When it comes to working on your files and making changes, you can always use git status to see what files have changes that haven’t yet been staged or committed. When a file has changes but hasn’t been staged yet, running git commit will not commit those changes, so it’s important to remember to stage any changes you intend to include in your next commit. Like the last example, files are added to the staging area by running git add.

Creating branches

Now, typically it is not good practice to be committing directly to the main branch. That’s what branches are for! A branch is basically a pointer to your project at a certain point in time. git branch -a displays any branches that exist in your local repository. To create a new branch, you have a couple options. git branch <new branch name> creates that branch, but doesn’t move you to be working in that branch. git checkout -b <new branch name> will create that branch and move you to be working in that branch. git checkout <branch name> can be used to move to another branch. Git recently added the command git switch specifically for switching between branches, but that will only exist in newer git versions, and using git checkout to switch between branches is still supported. So, what you use might depend on what version you’re using and your own preferences.

Viewing file statuses

Git also has some commands for viewing different file statuses. git diff without using additional options will display changes made to files that currently exist in the working directory. git diff –staged displays changes made to files that are currently staged. And git diff head will display changes for files in both areas!

Merging branches

Once you’re happy with your changes that exist in a branch, that branch can be merged into your main branch so that all your changes exist in the same place. We’ll get into merge strategies a little bit more later, but here are the absolute basics. You’re going to want to start in the branch you want to merge into, which is usually main. All that git merge does is it creates a commit in that branch that includes the changes from the other branch. In your command line this looks like git merge <other branch name> -m “<Commit message>”. Once you’ve merged, the other branch you’ve taken the changes from is safe to delete, but it doesn’t get deleted automatically. To do that, you can run git branch -d <branch name>.

Viewing your commit history

If you’d ever like to view a history of the commits in your project, you have plenty of options. git log has over a hundred different options for how to display this information. Without any options specified, git log displays each commit in the project’s history starting with the most recent. If your project has been worked on for a long time with a lot of commits, this can be a bit tricky to parse through, so you could run git log –oneline, which displays each commit with some information shortened so that it only takes up one line. There’s also git log –oneline –graph which also provides you with a visual representation of when any branch was created and when it was merged back into main. These are just a few options amongst many. If you’d care to look at a full list of what git log can do for you, you can find that here.

Shared Repositories

Working on a shared repository can be a little different, if mainly just because you have changes other than your own to worry about. But even when working in a shared repository, changes are always made first on your local repository and then pushed to the remote repository.

Setting up a remote repository

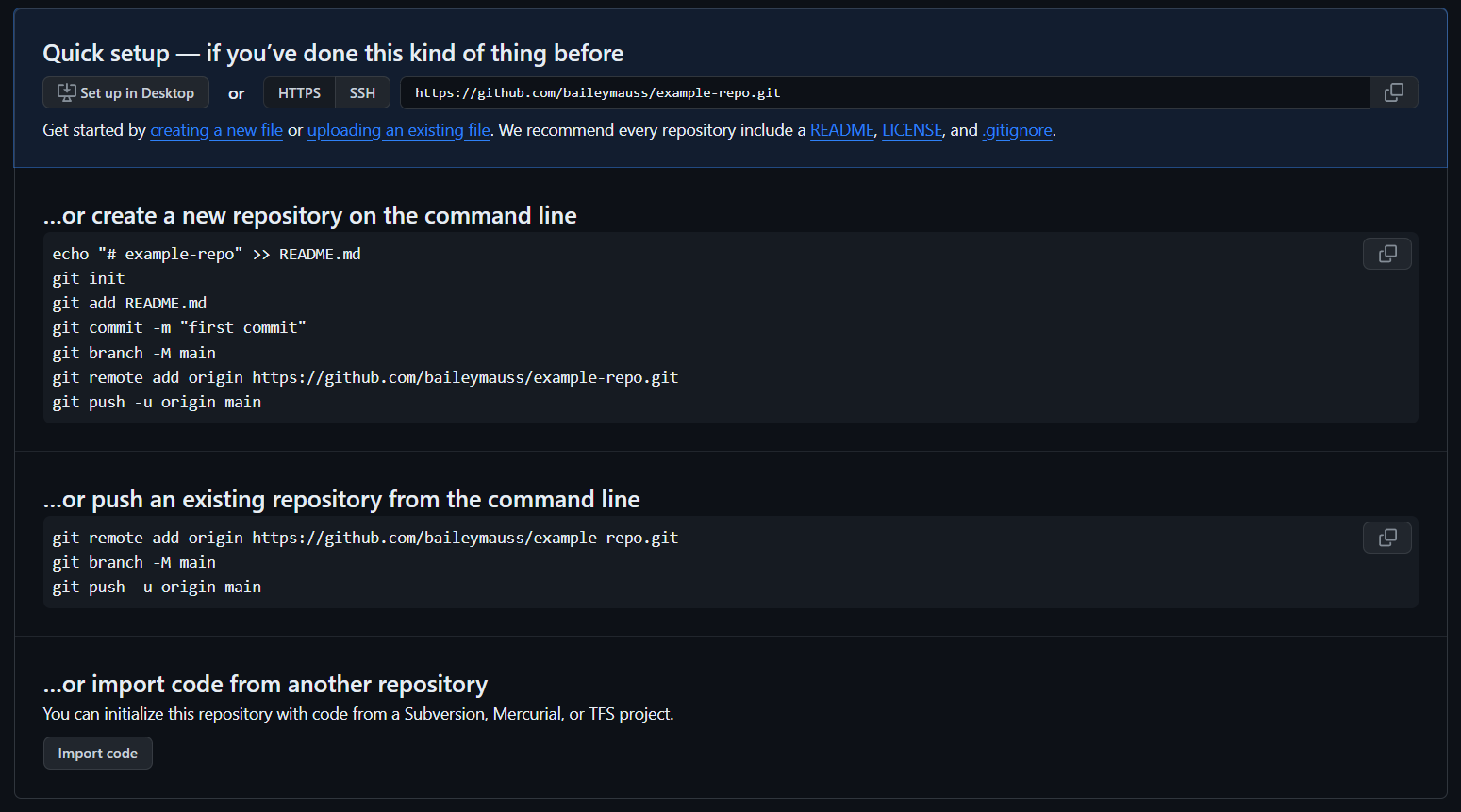

If you’re using GitHub (one of a few different code hosting platforms out there that can facilitate remote Git repositories, with its own set of additional features) when setting up a new repository, it will provide instructions for creating a new repository on the command line, or to push an existing repository from the command line.

This page is displayed after you’ve created the repository on GitHub with a name

This page is displayed after you’ve created the repository on GitHub with a name

git remote is used to create links between repositories, like local and remote copies. Without additional options, running git remote will display existing remote connections. If you want a little more information, such as the URL of the remote source, you can run git remote -v (for verbose). git remote has plenty of options available to manage remote sources. For example, if you wanted to link your local repository to a GitHub repository, you would run:

git remote add origin <GitHub repo URL>

Here, ‘origin’ is just the name we typically use for a remote repository that your local repository is linked to. ‘Origin’ also functions almost like a variable name, as once it’s defined we can just say origin to Git instead of the entire URL name. Technically, you could name it whatever you want, but origin is the convention most commonly used (and we see it in GitHub’s instructions). We have to define this connection so that Git knows they’re connected and can keep track of changes between both. It’s also worth noting that there are two kinds of remote connections that can be configured: one for fetching (or retrieving changes from the remote), and one for pushing (sending your local changes to the remote). These are often the same location, but they can be different, if you’d like.

Cloning a remote repository

If you want to get a copy of a project to work on, or others want to get a copy of your project, it’s as easy as cloning it. You’ll need the URL of the project, which if you’re working on GitHub it will provide you a URL based on what security protocol you’d like to use (HTTPS, SSH, or GitHub CLI). Using git clone is convenient too because it will also set up that remote connection. To do this, in your command line you’ll need to be in the location in your file system you want the project to be, as this will be the location the project files will be copied to. After that, you’ll need to run:

git clone <repository URL>

And you’ll have a full copy of the project locally that you can work on.

Sending local commits to the remote repository

When you’re happy with your changes in your local repository and want to send them to the remote repository so that other contributors can see them, we use git push. git commit, like we’ve been doing, operates on your local repository, but it doesn’t do anything to the remote repository. When you perform a push for the first time in your project, we have to indicate to Git where we want our changes to be pushed to. The remote repository won’t necessarily understand how branches on your local repository connect with its own branches, so at least the first time we push changes, we should use the -u option (for upstream). This tells Git the remote repository needs a remote tracking branch to link with our local branch, and creates it. Once that connection is established, we can just use git push going forward. This is branch specific, so if we were to create another branch locally and make changes there, we’d need to again use the -u option the first time we push changes. We also specify what connection we’re using to push changes (in this case, origin), and which branch on the remote repository we want our changes to apply to. With all of this considered, this is how we get the full command:

git push -u origin <branch-name>

Fetching and pulling commits from the remote repository

When other contributors make changes to the project and push them to the remote repository, you aren’t going to automatically have those reflected in your local copy. From time to time we have to bring those changes to our local version. If we wanted to retrieve the changes before merging them into our local copy, we could run git fetch to do that. git fetch by itself doesn’t really show you what exactly the differences are between the two versions, so if we wanted that information, we could use git diff. To use this in this situation, we would run:

git diff <local-branch-name> origin/<remote-branch-name>

This will compare the local branch to the remote branch. If your remote connection isn’t named origin, you’d replace origin with that name instead.

When you’re ready to merge the remote changes into your local copy, you’d run git pull. All git pull does is run git fetch and then git merge. This will retrieve any commits from the remote repository that our local repository doesn’t have and then incorporate them into our local copy.

Basics of merge strategies

Eventually when working on a project with different branches, there will be times we need to merge them to bring commits from one branch into another. Git has at its disposal different merge strategies to accomplish this, depending on what the history of the branches looks like. There are two basic types of merges that are used something like 95% of the time: a fast-forward merge and a 3-way merge. You don’t need to tell Git specifically to perform these when asking it to merge; it will look at your commit history and decide what strategy is applicable.

Fast-forward merge

A fast-forward merge is the most basic and straightforward type of merge. This kind of merge only works if you have a linear commit history between the two branches; basically, if you have a newer branch you’ve been making changes on but the older branch doesn’t contain any diverging changes. This kind of merge ‘fast-forwards’ the older branch to reflect the changes of the newer one, bringing the two to the same place.

3-way merge

A 3-way merge is an option even if the two branches you wish to merge don’t have a linear commit history (for example, both branches have commits on them that the other does not). This strategy uses 3 commits to create a new merge commit: the most recent commit on either branch, and the most recent ‘common ancestor’ commit the two branches share. Using these it’s able to bring the two branch histories together.

Rebasing

An example of a more advanced kind of merge (and it really is different from a merge, but accomplishes a similar end result) is rebasing. Rebasing takes two branches with a diverging history and creates a linear history for them, as opposed to the 3-way merge approach which brings the histories together but the past diverging history remains clear. It achieves this by taking the commit history of one branch and adding it to the timeline of the history of the other branch, making it into one straight timeline. A linear commit history can be advantageous: it looks neater, it’s easier to troubleshoot, and simpler to understand the commit logs. But it should also be understood that rebasing can be destructive. It permanently alters the history of the project, and there may be times you would really want the original history to be available to you. We’ll talk about rebasing more in depth in a future post, but for now understand you should probably only be rebasing your project if you know what you’re doing.

Merge Conflicts

What are merge conflicts?

When trying to merge changes, it doesn’t always go without a hitch. Often we will find merge conflicts we have to deal with before we’re able to merge. A merge conflict occurs when there are conflicting changes in the same contents of the same files between versions you want to merge. Git doesn’t know, and isn’t going to assume, which version of the changes you want to keep going forward. Some examples of some situations that might cause merge conflicts could be:

-Multiple people make changes to the same line in a file -One person deletes content in a file and another person makes changes to that content -One person deletes a file and another person makes changes to that file

These differing changes can absolutely exist in different branches of a project, but they become a problem when trying to merge one branch into another. Both versions can’t exist in the same branch. When this happens, Git will notify the second person making one of these conflicting changes that there is a merge conflict and it needs instruction on which changes to accept.

Resolving merge conflicts

In trying to resolve a merge conflict so you can proceed with your merge, Git will provide merge conflict markers to identify the exact lines in a file that are conflicting. All that we have to do is keep what we want, and get rid of what we don’t. Deciding which changes to keep is up to you (and probably your team, if you’re working in one). Once you’ve edited your files to remove any conflicting content, and any conflict markers, you can use add, commit, and push like normal.

Preventing merge conflicts (where you can)

Some amount of merge conflicts are probably not avoidable, but there are some things you can do to keep them at a minimum. Standardizing your formatting rules can really help avoid small, silly problems, as additional whitespace or different coding styles can be enough to cause a conflict. If you like, there are code formatters and linters you can use to make this as easy as possible.

Some other practices are advisable, too. Making small and frequent commits is much preferable to waiting until you have a whole load of changes. Merging and pulling changes frequently, too, is important, so any other contributors to the project can integrate your changes into the versions they’re working on, and vice versa.

It’s also important to just communicate when working in a team setting. If everyone is paying attention and understands who is working on what, it’s much easier to stay out of others’ way!

Modifying Commits

If you’re ever working on a project and realize you’ve made a mistake with a commit, this isn’t set in stone, especially not if you’re working locally. As a general rule of thumb, the only commits you’ll want to make changes to are ones that only exist in your local repository, as messing with commits on the remote repository can interfere with everyone’s work. But if you’re just in your local environment, you should be able to modify commits freely. We have a few different tools at our disposal depending on what we’re wanting to achieve.

Git amend

Using git commit –amend is helpful for making a quick fix to your most recent commit. It operates on the commit your HEAD pointer is pointing to, which should be the most recent commit in the branch you’re working on. HEAD does change when you change branches, so be aware of that. Using git amend enables you to make a change to the commit message, or add some extra files to the commit. This does permanently change the metadata of the commit, so don’t use this on any commit someone else is basing their work off of, only in your local repository.

Git reset

git reset has a few options depending on what you’re wanting to do with it.

git reset –soft takes a commit from the project history and moves it back to the staging area. This is good for situations where you might need to change or add which files are being staged for a commit, or if you need to regroup commits.

git reset –mixed, or just git reset, is the default option for git reset. This takes a commit from the project history and moves it back to your working directory. This is useful when you need to modify file changes or make more changes before proceeding.

git reset –hard takes a commit from the project history and throws it away entirely. This is a destructive command, and thus should be used with caution.

Git’s reflog

Git’s reflog can be used in some situations to actually retrieve deleted history. It has some limitations, as the reflog only includes local history and is time limited (by default, commits are only in the reflog for up to 90 days, after which they are seriously gone). The reflog is a log history similar to what you’d get from git log –oneline, but what it’s displaying is a history of where your HEAD pointer has been. Using the reflog, we can get commit IDs, which are needed if we want to retrieve an old commit we’ve discarded. Once we have this ID, we can use git cherry-pick to take that commit and place it back into our commit history, like so:

git cherry-pick <commit ID>

Conclusion

Well, we’ve just covered a surface-level view of what Git is and what it’s all about. This was long, but I learned a lot about the conceptual model of Git that no one had explained to me before, and hopefully you did too! I intend to follow this post up with another that will go more in-depth on some things that were referenced here. See you then!

-

Any time some content is enclosed with angle brackets ( < > ), that is intended to be replaced with the actual content when using this code in the command line ↩